~~~~~Encountering the Water Wolf~~~~~

In ‘Imagining Water in the Anthropocene, Astrida Neimanis argues that “what water is is inextricable from how we imaginatively produce it” (157). As such, in blocking out the ‘water wolf’, the Dutch people not only protect themselves, but also increase the perception of the water as a threat, which in turn increases the ‘need’ to control it. Furthermore, the continuation of such a representation of water is not productive for an inevitable future where water will become an increasing presence in the landscape. As such, cultural representations of water play an important role in redefining the materiality of water.

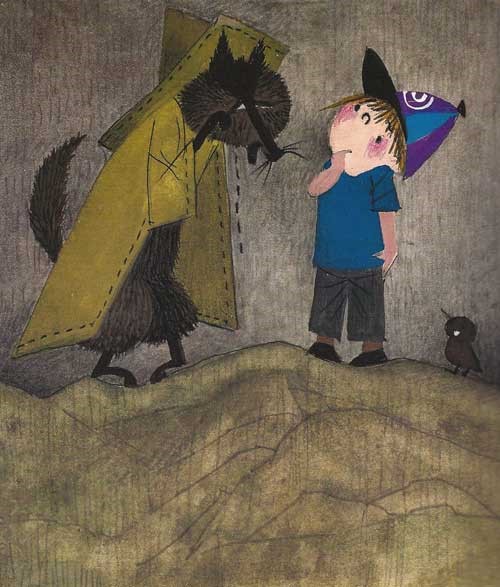

One reinterpretation of the ‘water wolf’ can be found Annie M.G. Schmidt’s children’s book ‘Pluk van de Petteflet’ (1970). Here water and wolf appear together in Pluk’s (the child protagonist) encounter with the “Heen-en-Weer Wolf” (118-28). Pluk meets the wolf when he needs to cross a river, although he is tentative as there is a rumour that the wolf may be a human devouring werewolf. This is reminiscent of the Dutch fear of the water ‘wolf’ due to it having ‘devoured’ (flooded) their land.

This discomfort of encountering the ‘object’ of fear is important in refiguring water. In ‘Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water’, Astrida Neimanis concludes that it is “in the borderzones of what is comfortable, of what is perhaps livable that we can open to alterity – to other bodies, other ways of being and acting in the world – in the simultaneous recognition that this alterity also flows through us” (111). In this sense then, the (Dutch) child, Pluk, must take a step outside of his comfort zone to allow him to experience the ‘water wolf’ in a way that is different to his preconception of it, and in order to move forwards.

Indeed, the original discomfort pays off for Pluk, as the wolf is revealed to be not a human devourer, but a mere wolf who once ate a goat because it was wrapped around a cabbage (all he really wanted was the cabbage). In this encounter, the water is no longer a wolf, and the wolf is no longer a threat, as the child is brought across the water without incident by the wolf. Furthermore, the wolf is overjoyed because Pluk is the first human who has wanted to cross the river on his ferry in ten years, and wishes to cross the river with Pluk multiple times. A positive conclusion of an encounter with water and wolf where as a result of not blocking out the ‘water wolf’, the (Dutch) child is not devoured.

A similar close encounter of the (Dutch) child with the water can be found in one of the early sequences of Bert Haanstra’s film ‘De Stem van het Water’ (00:04:38-09:21). In the sequence, a voice narrates that the Dutch “in order to survive just a little, need to learn to keep our heads above water, and that that learning can’t start early enough …” (my translation). Here then, the narration frames water not as something to be blocked out completely, but as something to be experienced with the body, with “early” suggesting that it must be experienced by a child. Continuing along, we view close-up shots of young children in a pool learning to swim, their faces a mixture of nerves, worry and fright. A sharp bodiless voice, presumably an adult, instructs the children in exercises to allow them to get to know the water. The camera focuses on one boy in particular who has trouble with the water, not wanting to put his head under. Here the child, like Pluk, is placed in an uncomfortable position with water as they experience it as a material body that surrounds them.

At the end of the film we return to the boy at the pool again (01:20:15). As we watch him leap into the deep end of the pool and swim confidently to the other end, we can conclude that he is no longer afraid. As the child swims, dipping his head in and out of the water, we see him not fighting against, but moving along with the water. As such, the (Dutch) child has again taken a leap out their comfort zone and realised that the water is not a ‘wolf’ that will somehow devour it. Furthermore, in physically experiencing the materiality of the water, the child physically embodies this knowledge.

In a similar stream, to return to Neimanis’ ‘Figuring Water In the Anthropocene’, she also argues that “if water is an idea, it is a material, embodied idea” (184). As such, in order to change the conception of water, water must be physically encountered differently than before. And this is precisely what occurred in 1993 and 1995, when rising water levels caused local evacuations, reigniting a consciousness of water in the Dutch (Van Koningsveld et al. 2008; Van Der Vaart 2014). It can be reasoned then that as a result it was brought to attention that a conceptualisation of water as a threatening creature to be kept out was not productive in a future of climate change and sea level rise. As such, this called for a more productive strategy for dealing with the water.