By Ella Bailey

Immigration and Censorship in the Dutch Republic : The Case of Spinoza

“Be not astonished at new ideas; for it is well known to you that a thing does not therefore cease to be true because it is not accepted by many” – Spinoza

In the seventeenth century Dutch Republic, immigration and a lack of effective censorship with regard to the publishing and circulation of books were inextricably linked. The United Provinces offered intellectual freedom and thus formed a publishing centre for thoughts which had been censored elsewhere, as well as providing refuge for those whose beliefs resulted in persecution in their motherland. While the States General did at times issue decrees and proclamations to stop the circulation of texts that were blasphemous or potentially damaging to the state, such measures were not always effective in preventing the texts from entering the public sphere (Hoftijzer 9). As a result, many scholars and thinkers from across Europe chose to make the region their home, including French philosopher René Descartes who remained for two decades. Perhaps one of the most famous individuals to test the limits of this intellectual freedom was the celebrated Dutch philosopher Benedict de Spinoza, who became one of the few censored authors in the liberal publishing climate of the Dutch Republic (Van Der Deijl 207). The son of Jewish immigrants who settled in Amsterdam following the Portuguese Inquisition, Spinoza was one of many Dutch citizens with an immigrant background who grew up in the United Provinces during its so-called Golden Age and can be considered an example of the fruit of immigration for the Dutch publishing industry. He benefitted from the aforementioned lack of effective censorship and intellectual freedom which prevailed in the region at the time, and his writings found an audience among a fortunately ever growing literate public (Hoftijzer 4). In this essay it is my intention to use Spinoza as a case study in order to discuss how immigration, coupled with a lack of effective censorship, contributed to the prosperity of the publishing industry during the Dutch Republic’s Golden Age. My research will thus be divided into two parts. I will begin with a brief account of Spinoza’s life, the religious migration of which his family was a part and the contribution of Jews to the printing industry more generally before exploring the environment that existed in the Dutch Republic at the time in terms of censorship and intellectual freedom, namely with regard to Spinoza’s first major work and one of his most influential treatises: the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670).

Jews in the Dutch Republic

As previously mentioned, Spinoza’s family arrived in the United Provinces following the Portuguese Inquisition. Spinoza’s paternal grandfather had previously relocated to France with his wife and children but they left in 1615 and moved to Rotterdam, the same year an edict by Louis XIII branded Jews enemies of Christianity and expelled them from France (Woods 64). The Spinozas were not alone. Between 1600 and 1800, an estimated 600,000 people moved to the United Provinces and about a quarter of these were political or religious refugees (Jan & Leo Lucassen 34).

The latter group included southern Dutch Protestants, French Huguenots, Jews from German and Polish lands as well as Iberian Jews (34). In the seventeenth century, immigrants accounted for approximately 8 percent of the overall Dutch population, while in certain Holland towns up to 30 or even 40 percent of the local population were immigrants (Mijnhardt 128). The population of Leiden, for example, multiplied sixfold between 1580 and 1672 (Jan & Leo Lucassen 35). Some 2,000 Iberian Jews settled in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century, and despite being excluded from almost all commercial guilds, except for that of the pharmacists and brokers, their trade contacts in the south and their capital ensured they enjoyed an influential economic position and they played an important role in the ascendancy of the Dutch Republic (36). In the Republic’s capital, a Jewish community several thousand strong (when the other non-Iberian Jews are taken into account) developed over the course of the century, and it became the European centre for Jewish printing with a successful Jewish book business in addition to being the location of the first Yiddish newspaper (Pettegree & Der Weduwen 334). The Sephardic Jewish community (of which Spinoza’s family was a part) worked in the printing, silk, tobacco, sugar and diamond trades, and were prominent brokers in the growing stock market (334).

Left: Interior of the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, Emanuel de Witte, 1680 (Source: rijksmuseum.nl)

Just a few years before Spinoza’s birth, in January 1627 the printing of the first book from a Jewish press in Amsterdam had taken place (334). The previous year, Menasseh ben Israel – a Portuguese Jew and one of the most influential Jewish scholars at the time – had founded the first Jewish print shop in Amsterdam. Over the next three decades he would print more than seventy five works in Hebrew, Yiddish, Latin and Spanish such as grammars, Bibles and books of pious study along with scholarly works he had authored himself and translated into Latin (335). Jewish printing in Amsterdam began to flourish when non-Jewish traders showed their interest, and Israel’s new commercial relationships with the bookseller Hendrick Laurensz, the publisher Johannes Janssonius and the Blaeus ensured that his publications were available across Europe (336). With its large Jewish population, Poland was the biggest export market, while in the Baltic region Jewish books were increasingly traded (337). Unfortunately for Israel, while Laurensz, Janssonius and the Blaeus helped make his name and contributed to the reputation of the Jewish community in Amsterdam, they also held on to the majority of the profits (336).

A Dutch book printing office in the mid 17th century, engraved by Abraham von Werdt (1594-1671)

Spinoza too came from a trading background. Young Baruch de Spinoza, born into a prominent family in Amsterdam’s Portuguese-Jewish immigrant community in 1632, left school at seventeen to help run the family’s importing business. Their specialty was the importation of dried fruit (Nadler). His father was an important merchant and eventually served as one of the directors of the city’s synagogue (Popkin). A few short years later at the age of 24, Spinoza was summoned before a rabbinical court and solemnly excommunicated for “monstrous deeds” and “abominable heresies” (Mijnhardt 126). This was the most radical sentence available to his religious community, and while it is not known exactly what these heresies consisted of, one can hazard a guess that he had already begun to articulate the ideas that he would be remembered for as an important radical of the Dutch Enlightenment, such as the denial of the immortality of the soul and the rejection of the idea of a providential god (126). Following this, Spinoza Christianized his name to Benedict (though there is no suggestion that he became a Christian) before moving to the village of Rijnsburg near Leiden (Strathern 24). There he lived in a modest cottage, supporting himself by grinding lenses while developing his philosophical ideas. He then relocated to Voorburg near The Hague in 1663, where he lived for the rest of his life and wrote his most influential treatises (Mijnhardt 127): Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (published 1670) and Ethics (published posthumously). Already from the 1660s, Spinoza had been sharing his subversive ideas among a wide circle of friends and his ideas were known to many people, including Joost van den Vondel who wrote about the TTP. After the publication of the TTP in 1670, Spinoza was recognized as a significant intellectual figure and found himself in the company of professors, diplomats, and writers of great renown (Popkin). He died in 1677 of consumption that was likely aggravated by the inhaling of glass dust from grinding lenses.

Censorship in the Dutch Republic and the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

It is important to note that censorship in the Dutch Republic during Spinoza’s lifetime was merely repressive, that is, books could be censored only after publication. This allowed printers to take greater risks as there was no preventive censorship, which would have required publishers to first present a copy of their work to a local sensor for approval (Pettegree & Der Weduwen 327). Furthermore, censorship efforts were almost irreconcilable with the decentralized political structure of the Dutch Republic. A book could be banned in Utrecht, but not in the rest of the country; a printer could be banished from one province, and simply re-establish himself in the next (327). However, the absence of any centralised censorship did not prevent Dutch authorities from acting forcefully at a local level if they considered it necessary (Van Bunge 152).

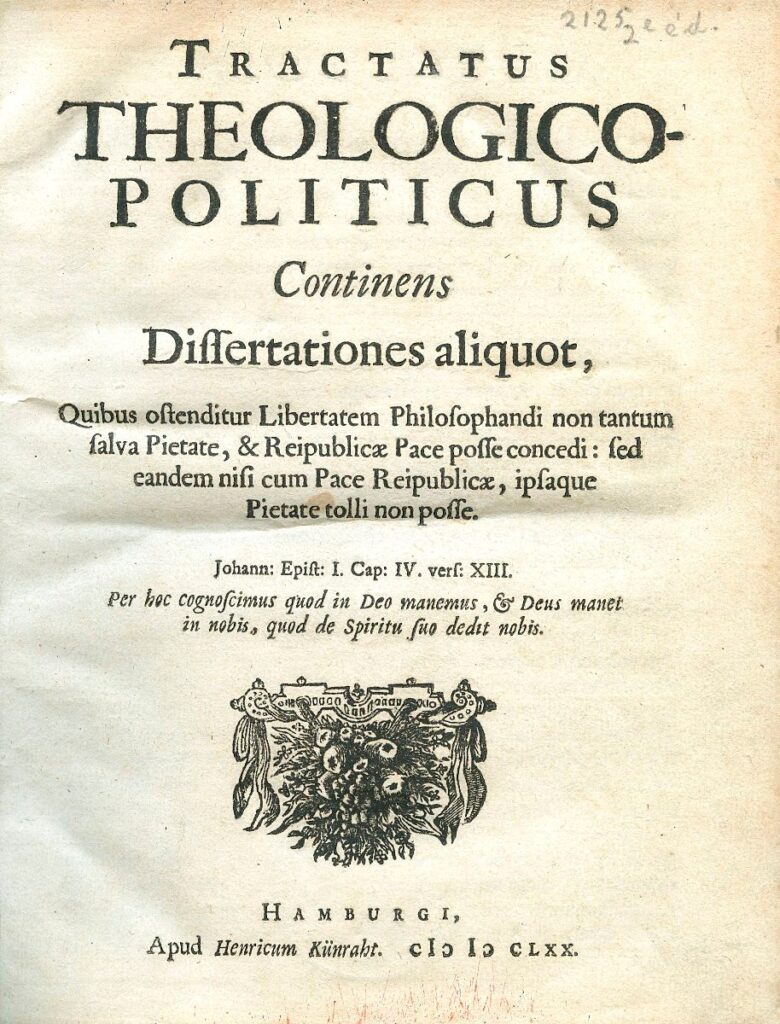

When Spinoza had his Tractatus Theologico-Politicus published he was careful to do so anonymously under the name of a fictitious Hamburger publisher and in Latin, but his authorship was soon recognised. In this critical analysis of the Old Testament, Spinoza articulated his view that most Biblical laws were actually the laws of a desert people and therefore no longer applied to contemporary society. He also defended republicanism and democracy, believing that the role of the church should be limited within the state. Left: Title page of the TTP with fictitious Hamburger publisher.

The TTP was an immediate bestseller and only made him more notorious than he had been prior to its publication (Prokhovnik 237). The TTP was one of the few books to be officially banned in the Netherlands during this period, though it could be bought easily and it was soon the topic of heated discussion throughout Europe (Popkin). The same year it was published, the TTP was referred to as the most blasphemous book ever written at the Synod of North Holland (Van Bunge 146). Spinoza’s TTP was reprinted several times in the 1670s (Pettegree & Der Weduwen 331) and before the end of the century five editions of the Latin original, most of them with false title pages and fictitious imprints, made it to the book market despite the official ban in December 1673 (Van Der Deijl 208). The use of false imprints to keep the publisher’s name secret as well as the use of imagined places of publication was a favoured practice of Dutch publishers and used for numerous controversial or prohibited works (Pettegree & Der Weduwen 327). The credit for the book’s successful circulation has been attributed to Spinoza’s publisher, Jan Rieuwertsz, and his publishing strategies (Van Der Deijl 209). Rieuwertsz stood at the centre of a large network of unorthodox publishers who provided an outlet for freethinkers to voice their views. Spinoza and Rieuwertsz’s other clients were able to debate, read, and buy books in the safety of his publishing house (Pettegree & Der Weduwen 331).

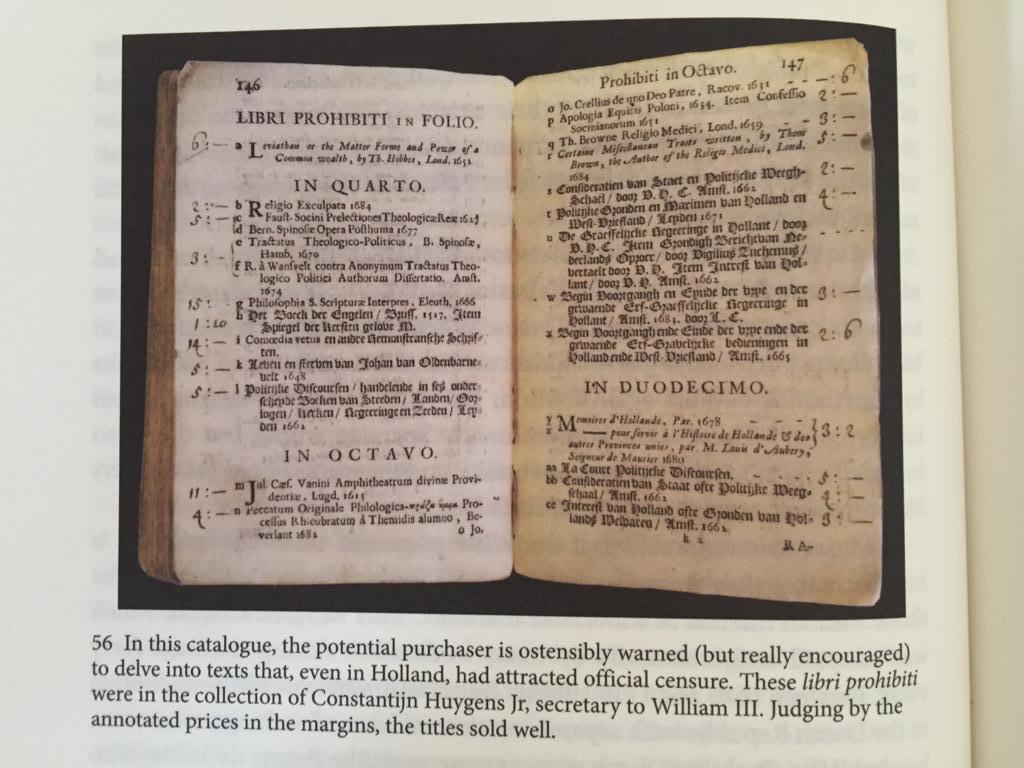

Censorship, as it turned out, was excellent publicity. This fact was even articulated by Grand Pensionary Jacob Cats who wrote, ‘unvirtuous books are sought after all the more, and what is forbidden is bought with the greatest desire’(327). The persistent attacks by Reformed ministers against their unorthodox opponents only encouraged the spread of non-conformist ideas, driving demand for works by Socinian (which was often synonymous with Spinozist), Remonstrant and freethinking authors and turning them into coveted ‘libri prohibiti’(332).

In auction catalogues the potential buyer was ostensibly warned (but really encouraged) to look at texts which had attracted official censure (326). The sections of the auction catalogues containing these lists of censored books generally comprised twenty to forty titles each time and on occasion included those by Spinoza (325).

They were identifiable either by being unmarked but clearly separated from the other titles, by appearing under a section titled ‘Libri Sociniani’ or by appearing under the more obvious heading ‘Libri Prohibiti’, sometimes accompanied by the phrase ‘to be sold in private, in a closed room, at the end of the auction’(325). Booksellers such as Johannes du Vivié believed that distinguishing the libri prohibiti within the catalogues would increase their value, and based on prices in surviving documents he was not proved wrong (326). Spinoza’s controversial ideas did not only create demand for the clandestine publication of his works under various guises with fictitious imprints as well as the compilation of catalogs selling his works as libri prohibiti. The knock on effect of the contentious nature of his philosophy was that ministers and theologians had to produce their own texts refuting his ideas which would be printed and disseminated thus further contributing to the prosperity of the publishing industry. If they did not react, the public could interpret this as meaning that the ministers did not have answers to the questions raised by Spinoza, or more dangerous still – that they agreed. Thus, immediately after its publication in 1670 the treatise was strongly condemned by ecclesiastical, civic, and academic authorities alike (Israel 275-76). As noted by Pettegree and Der Weduwen:

Publishers thrived on the literature of religious controversy, and not only by selling subversive books. After all, there were more anti-Socinian works printed in the Dutch Republic than Socinian works, and refutations of Spinoza were penned by leading theologians of all Protestant denominations. (Pettegree & Der Weduwen 332)

The first known official response to the TTP by the Dutch Reformed Church authorities was on April 8th 1670, when the outraged Utecht kerkenraad reported on the work and urged the city’s Burgomasters to make appropriate measures against the treatise. This was soon followed by violent reactions in other towns including Leiden, Haarlem, Amsterdam, The Hague and Schieland (Van Bunge et al. 25). Furthermore, freethinkers such as Spinoza provided work for unorthodox publishers. While there was no preventive censorship as such, some publishers did report their authors to the authorities after reading the work as it was coming off the press. One such example was the publisher Everardus van Eede who received no punishment for printing (or rather, beginning to print) the second work of Spinozist Adriaan Koerbagh in 1668, since it was he who reported Koerbagh. This is why unorthodox publishers like Rieuwertsz received so much work from their network of Remonstrants, Mennonites, Socinians and Spinozists. Evidently, it was worthwhile to find a publisher who could be trusted and who was committed to the cause (Pettegree & Der Weduwen 333).

Interestingly, despite the fact that the TTP was banned and Spinoza’s authorship of the treatise was common knowledge, he was never subjected to any legal investigation (Van Bunge 152). Van Bunge suggests this was due to the fact that the Dutch Reformed Church still considered Spinoza a Jewish author, thus they could not be held responsible for his delusions (152). Spinoza’s TTP had nevertheless been able to circulate in various Latin versions for three years and become a bestseller before it was prohibited by the States of Holland, and the existence of clandestine versions of the text could not be completely thwarted after the ban. By 1677, in the context of controversial publications even the Grand Pensionary of Holland Gaspar Fagel admitted ‘in such a free country as we inhabit it is impossible to arrange everything according to one’s wishes, so it is best to defeat such books by ignoring them’ (Pettegree & Der Weduwen 331). This strategy, however, does not appear to have been applied to Spinoza. In the narrative on the intellectual freedom of the Dutch Republic, Spinoza remains one of the anomalies as one of the few authors to be censored in what was an otherwise liberal publishing climate compared to other European states (Van Der Deijl 208). Evidently, his ideas were contentious enough to warrant more than just passive indifference from the authorities. However, as we are aware, this censorship was not completely effective and Benedict de Spinoza managed to make a notable contribution to the prosperity of the Dutch publishing industry in the seventeenth century regardless thanks to the demand for libri prohibiti, the strategies of his trusted unorthodox publisher Rieuwertsz, and the many refutations written and published by leading theologians in response to his treatise.

As a member of the Jewish community (at least for the first decades of his life) Spinoza was also part of a larger group that played a significant role in establishing the reputation of both the Dutch Republic and its capital as a centre for Jewish scholarship and publishing at a time when such activities were increasingly restricted for religious minorities on other parts of the continent. A statue in his honour was unveiled in 2008 at Zwanenburgwal, close to where he once lived. Its inscription – a quote by Spinoza – reads ‘Het doel van de staat is de vrijheid’ (‘The purpose of the State is freedom’).